Anatolia

The Turks, living in this territory for a thousand years, have inherited some part of the culture of

every civilization which flourished here since prehistory. They have evolved a synthesis derived

from the cultural legacy of Anatolia, from the culture they brought with them from Central Asia,

and from the Muslim religion. Their talent for synthesis and their ecumenical character have

enabled them to blend these three strands together. The imprint of these heritage’s is readily

visible in the cultural fabric of Turkey today. You yourselves accept that your own civilization

originated in Mesopotamia (where civilization flowered for the first time), then Anatolia, the

Aegean basin, and Rome. We have at least as much right as you to adopt these ancient civilizations as our own, since they are those of our own land. In looking at our history as an insider of Anatolia, we can claim to have lived on this land since the beginning of the Anatolian civilizations, for both culturally and demographically the preceding civilization has each time been carried over, at least to a certain extent, into the succeeding one.

It was we, therefore, who brought about the Neolithic revolution. The Sumerians were also a

people whose language was agglutinative like ours and had the most important word, namely God, in common with us. The Anatolian Civilizations were created by indigenous peoples, Hattis,

Hurrians, Lydians, Lycians, Sea Peoples, and Minoan Cretans. Indo-European peoples such as the Hittites, the Luvians, and later the Ionians and the Phrygian s, were assimilated by the indigenous peoples, who had been already civilized.

The Hittites succeeded in establishing an empire which was the first Anatolian political union. It

had the same geopolitical core as the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires, and suffered the same fate.

At Troy it was we Anatolians who resisted the foreign aggressor, with “the help of the Anatolian gods” and of men gathered from all corners of Anatolia, who did not even speak the same language.

Later we defended ourselves against the crusaders, then in 1915 against the Allies invading the

Dardanelles.

Homer – our countryman – in the ninth century BC signalled the beginning of what would later be

called `the Greek miracle’ in Anatolia. This `miracle’, which was created in the first place by

Anatolian `physicists’, crossed the Aegean Sea to mainland Greece. Science and knowledge of the cosmos developed on our shore of the Aegean; ethos, philosophy, and theatre on the other shore.

Both shores gave rise to cities which nurtured political and economic liberties.

The appearance of the Greek miracle in Anatolia following Crete, which was the cultural extension

of Anatolia, was predictable since civilization had been born in the East and moved to the West.

The Greek Revolution in 1820 prompted European historians to regard mainland Greece as the

starting point of their civilization, overlooking the cradle of the miracle. They did so because the

source was Anatolia, our country inhabited by Turks.

After the Greek miracle Anatolia was occupied by the Persians coming from one side and the

Macedonians coming from the other. Eventually they brought nothing but ruin and caused Anatolian science to lie dormant until the Renaissance. The remnants of this cultural heritage can be found today in Anatolian folklore, myths, fables, dances, clothes, houses, carpets, cooking, music, and common words. In this sense no one in western Europe can claim to be as Aegean as ourselves. To accept this fact, however, means that one first has to give up an ethnocentric perspective of history.

Later came the Roman Empire. Anatolia was its most important province, and her culture and

civilization revived accordingly. She became aware of belonging to the whole Mediterranean basin.

Christianity, which was just beginning at this time, received its name at Antioch, and by the efforts

of Paul of Tarsus-another of our countrymen -was spread throughout Anatolia where the first seven churches were built. The apostle John lived at Ephesus and his Gospel begins with a reference to the logos, a concept of Heraclitus. The pioneers of the new monotheistic religion encountered the superior rational culture of pagans for the first time in Anatolia. The classical culture was swept away by Christian humanism but only after Christianity had absorbed the ideas of the Greek philosophers Plato, Aristotle, and Plotinus, as well as the folk culture.

With the advent of the Eastern Roman Empire, monotheism became the State religion, and

Anatolian political unity was restored. This Empire had to struggle against the Sassanids to the east, the Muslim Arabs to the south, and the barbarians to the west. The Balkans became converted to Orthodoxy. The Christian religion, which had been born here, underwent an internal evolution. With time it became differentiated from Catholicism whose evolution unfolded in a different social, political, and cultural context.

The system of pronoia (fief-timar), an original creation of the Eastern Roman Empire, eventually

degenerated, resulting in the ruin of its agriculture. The Capitulations weakened its economy and

bubonic plague decimated its population. In the end the Empire was surviving only through the

efforts of its shrewd diplomacy. Everything changed in 1071 with the arrival of the Seljuk Turks,

followed by the Franks in the role of crusaders. Both of these groups wanted to fill the void left by

the decline of Byzantium.

Ostensibly the aim of the Franks was to liberate the Holy Places and Byzantium from the Muslim

Turks. Indeed, they captured the Holy Places but held them only for a short time, and soon showed scant sympathy towards the Orthodox Christians. In 1204 the fourth crusade captured

Constantinople. Throughout this period of two hundred years the Turks had gradually been settling

in Anatolia. The Anatolian peoples and the Muslim Turks, by living together on the same land during this time, gradually achieved a new cultural synthesis. A large contribution to this process was made by the Turkish mystics, Mevlânâ and Yunus-our countrymen.

Turkish philosophers had preceded Turkish warriors in the Middle East by two centuries, and the

conquest of Constantinople by five centuries. AI-Fârâbî, the first of these philosophers, was an

Aristotelian. Both he and, later, Avicenna attempted to create a synthesis between Greek

rationalism and Koranic dogma. Their method was dialectic, teaching as they walked with their

students.

Other Muslim philosophers included not only celebrated Platonists and Aristotelians but also natural scientists, influenced by the Anatolian Physicists. Muslim mystics were also influenced by

Neoplatonism.

The works of all these philosophers, who kept Greek philosophy alive and enabled it to develop,

were translated into Latin and, through Spain and Sicily, reached the rest of western Europe, where they contributed much to the Renaissance. Had Europe been fair, it should have added the word Islam to the equation which represented its cultural background to make it ‘Judeo-Christian-Islamic, Graeco-Roman’.

Islam, like the two other monotheistic religions, bears witness to Abraham. In spite of their

universal nature all three were revealed to the Semites and, though different, have points in

common. The Turks, just as much as the Indo-Europeans, were foreigners to the Semites. Islam, like Judaism and Christianity, was eastern Mediterranean in origin.

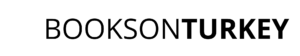

Ottoman Empire

That is why, when the Ottomans prevailed, the Byzantine philosophers were convinced that the

members of the two creeds could be reconciled. The hostility shown by the crusaders towards the

Orthodox Church merely facilitated the transmission of the Byzantine legacy to the Ottomans. The

Ottomans subsequently inherited many Byzantine institutions, either directly or through

intermediaries such as the Sassanids-Samanids, Omayyads and Abbasids, Grand-Seljuks, and

Anatolian Seljuks.

If the Roman Empire represented the extent of the spread of Western culture, it also played a no

less important part in the structure of the Ottoman Empire. In addition to the contribution of the

Greeks, whether converted to Islam or not, the Ottomans received from the East Roman Empire

the entire Balkan heritage, including Greece herself.

By 1517 the Ottoman Empire included all the European territories which had previously been

Byzantine, except for the south of Italy. The Patriarchate, newly endowed with political powers and

uniting previously separate Churches, became more powerful than it had ever been in the time of

Byzantium.

The zenith was reached at the end of the sixteenth century when the decline of the Empire began.

Factors which contributed to the downward trend were the growth of maritime trade by European

countries following voyages of exploration, the Capitulations, inflation, deterioration of the

ecosystem, the collapse of fundamental institutions such as the fief and the corps of Janissaries,

and the prohibitive cost of defending an oversized Empire.

In an attempt to regain the grandeur of the time of Suleyman the Magnificent, the first reforms in

the seventeenth century proposed a restoration of the previous conditions by strengthening the

central authority. Westernization reforms began only after the defeat by the Russians in 1774,

ratified by the treaty of Küçük Kaynarca.

The real basic cause of the decline of the Ottoman Empire was the fact that western Europe

managed to push forward its own evolution-by means of the Renaissance, the Reformation, the

French Revolution, liberalism, and the industrial revolution-to the stage of the nation-State, a

development process different from and more successful than that pursued by the Ottoman Empire.

Like Byzantium, the Ottomans never experienced a Renaissance period, for both remained loyal to the mission and the nature of the universal state.

The initial power of the Empire was itself the cause of delay in launching westernizing reforms.

When they eventually came they began with the army. The judicial system was then modernized by gradually withdrawing the administration of justice and education from the control of the religious authorities. Then ideas of homeland and liberty made their appearance, and an attempt was made to limit the power of the Sultan. However, the reforms were not carried through due to the rebellions of Christian communities in the Balkans, inspired by nationalism and stirred up by Russia, and the wars which followed.

The Capitulations evolved into a means of colonization. The Empire found itself in debt and could

not repay what it had borrowed. When bankruptcy came, its revenues were confiscated. Except for a short period, successive governments did not pay enough attention to the economy.

After the loss of the Balkans, Islamism and Westernism competed to give the Empire a new identity.

Turkey and Europe