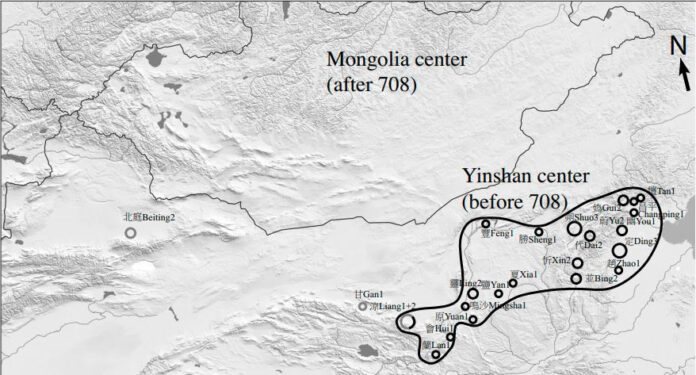

Map of the Turkish raids on Northern China before and after 708 AD

Fig. 2. The changing pattern of Turkic raids on Chinese prefectures before/after 708 (682–744). Black line and circles: Turkic raids before 708; grey circles: Turkic raids after 708 (Liangzhou was raided in both periods). Size of circles proportional to number of raids, indicated after the name of the prefecture.

This map is an important proof of a profound geopolitical evolution in the second Turkish empire, unnoticed so far. Before 708, this empire prospered South of the Gobi and a big part of its elites’s wealth came from the yearly pillages on Northern China. The economic basis of the imperial elites after 708, that is after the Chinese managed to build forts north of the Huanghe loop and consequently expelled the Turks from their century-old basis south of the Gobi, was very different. There were no longer any raids on Northern China. They had to rely only on the Mongolian steppe and its wealth. This in turn opens the possibility of a wholly new interpretation of the Orkhon inscriptions, as an attempt to deal with this catastrophic new situation, a passionate plea to make the best of a bad bargain. Before 708 the Turks were very happy to be far away from the Ötüken. This map was published on p. 457 of “Away from the Ötüken : A geopolitical approach to the 7th c. Eastern Türks,” in J. Bemmann, M. Schmauder (ed.), The Complexity of Interaction along the Eurasian Steppe zone in the first Millennium AD, (Bonn Contributions to Asian Archaeology, 7), Bonn, 2015, p. 453-461. More in the article and pdf of the article available on demand!

寸Feng1

曰Ling2

嗕Lan1

㵤Liang1+2

䓀Gan1

⢷Xia1

㚼Shuo3

ẋDai2 ⭂Ding3

並Bing2

⩗Gui2

壇Tan1

勝Sheng1

⍇Yuan1

渥Yan1

哂Yu2 幽You1

㖴⸛

Changping1

嵁Zhao1

㚫Hui1

沜㱁Mingsha1

⾣Xin2

北庭Beiting2

Yinshan center (before 708)

Mongolia center (after 708)

When placed in its proper geopolitical setting, we see that the Chinese policy at the end of the sixth century was to create a buffer zone and to declare this zone an empire as if an actual Eastern Turkic Empire had survived after Turan’s death. The historiographical trap is here: the Chinese made the better of a bad bargain because Tuldikh simply failed to meet the expectations. They claimed that their champion was the Great Qaghan while in fact he has been very much ejected from the political scene in the steppe, in which the Tiele and the Western Empire played the main roles. When chaos erupted in internal Chinese politics, this buffer zone indeed turned into a powerful Southern Empire under Shibi and Xieli. This, however, was a completely unexpected development which proved if anything that it was extremely dangerous to make use of this northern Ordos region to settle nomadic allies; in Antiquity the Ordos has been the very first region where the Xiongnu people grew powerful. The Eastern Empire under Shibi and Xieli, a very long-stretched empire following the Chinese frontier towards the east, lived by pillaging northern China. There was no apparent attempt to put the court back to the north of the Gobi. It was very different from the first Turkic Empire and cannot be seen as a legacy of this first empire, but as a consequence of the Chinese answer to the complex Ashinas policies.

This takes us to the end of the seventh century, to the revolt of Qutlugh (Qutluγ) in 682, who was soon to become Ilterish Qaghan (Fig. 2). There is no question that the revolt was rooted in the south. The base of the Türks were the Yinshan and the Black River region, that is the region around Hohhot: Czeglédy demonstrated in 1962 that the Čoγay-quzï/yïš of the Tonyuquq inscription, where the rebels rallied and created their empire, were none other than the Yinshan (Čoγay has the same meaning as Yin, shaded, northern slope of a mountain) and that the capital of Qaraqum of the same inscription is Heisha cheng of the Chinese text (both meaning black sands), a settlement situated on the northern slopes of the Yinshan (Czeglédy 1962, 55–56)8. A simple list of all the topographical names mentioned in the Chinese sources shows beyond any reasonable doubt that, speaking of the geography, the second Eastern Empire was initially a revival of the empire of Xieli. From the Yinshan they raided over and over again all the northern prefectures of China during one generation (lists of raids in Liu 1958, 433–439; Skaff 2012, 302–312).

However, this is clearly described as a feature of the past in the Orkhon inscriptions. The recurrent message in these texts is the praise of the Ötüken, the residence of the Turkic qaghans in the final years of the Turkic Empire. Thus, one century after Tuldikh’s flight from north to south an unnoticed major, reversed geographical shift from south to north must have been taken place in the organization of the second Turkic Empire.

The reason clearly lies in a devastating strategic defeat of the Türks, which could not be explicitly recognized in such propaganda texts as the official inscriptions: in fact the Türks were forced to leave the Yinshan by a military move of the Chinese. In 708 the Chinese army cut the Yinshan Türks from the south by establishing three fortified points north of the Huanghe. We would like to know much more about this move but the text is not precise (Jiu Tangshu 194a: 5172; Liu 1958, 169). As the Yinshan and the Hohhot Valley have been the heart of the Turkic power since Tuldikh, this Chinese advance in the context of a revived Tang dynasty modified the balance of power. The consequence was immediate and we see a complete end to the annual raids of the Türks on the Chinese northern frontier. Never again would they come to pillage the prefectures of the northern Ordos region or northern Shanxi. The economic strategy of the Türk Empire had once again to change.

Such efficiency of these three fortified points is in a way quite mysterious. Qaraqum was on the other side of the Yinshan and no text mentions a direct conquest of the Yinshan proper. The Türks were not actually expelled from the Yinshan but left them. Maybe they were now too close to the Chinese border for it to be safe for the court. Or it might be that the Yinshan themselves were insufficient to sustain an actual imperial center if it was cut from the Huanghe and Heihe agricultural plains, or/and the raiding hinterland further south9. Conversely, the complete end of the raids after the building of these three forts even in regions much farther east along the frontier, which might have been reached from the north, suggests that in fact the Yinshan were the point of departure of the previous eastern raids, not the north.

However, this strategic defeat, whatever its economic and political importance, was mitigated by the evolution of the empire under the influence of Tonyuquq. Contrary to the early decades of the seventh century, the qaghans, and especially their main counselor Tonyuquq, did Show interest in the northern part of their empire before having to leave the southern part in 708. The chronology of this conquest of the north is not firmly known, it should have been within the reign of Ilterish (682–691), maybe in 685 or 686 before the great eastern campaign of 687 in Hebei – the conquest of the Ötüken is mentioned in Tonyuquq’s inscription just before some raids in Shandong up to the sea10. The importance of the northern part of the empire as a center of power is likewise unknown: Tonyuquq, who wrote after the events to defend his ideas, should be read cum grano salis when he noted that he “led the [qaghan?] and the Türk people to the Ötüken land”). What becomes clear, however, is that most of the activities of Ilterish Qaghan were concentrated to the south and east of the empire, not in the north: out of 19 raids attributed to Ilterish by Tonyuquq only five were against the Oghuz, and the first of these might have

taken place south of the Gobi. The north was first of all Tonyuquq’s domain and it is from there that he directed raids toward the Qirqiz and the On Ok: as Tonyuquq wrote himself “I settled in the Ötüken land”, not the qaghan.

Qapaghan Qaghan (691–716) had a broader vision and much more means: in 698 we seefor the first time the words 黑紗南庭 “Southern court at Qaraqum” in the Chinese sources (Jiu Tangshu 194a: 5169; Liu 1958, 162). Clearly in 698 a situation that had lasted over almost one century ended and the empire of Qapaghan was now established – as was the empire of the first Türks at its climax – on both sides of the Gobi. However, this was to survive only for a very short period as the Chinese move of 708 put an end to it. Having to withdraw to the north, and having no longer the usual resources, Qapaghan frantically tried to submit all unruly tribes in every direction except for the south. He used the Ötüken as a base, only to be killed a few years later in 716. The great 711–712 expedition to the west might have been triggered by the necessity to find an alternate place for pillages as China was now out of reach.

So it was up to Bilge Qaghan and Kül Tegin to make the best of a bad situation. In this regard, the message of the Orkhon inscription is pure political propaganda, and a close look at what they actually say does confirm this interpretation. When Bilge Qaghan inherited the throne, or rather took it from his cousin, the Türks were weak, poor, and desperate. According to the Or khon texts, they had had to migrate to the west and the east. These texts are long political appraisals of the Ötüken and Orkhon regions as opposed to the Čoγay mountain and the Tögültün Valley, because the relocation from the south was not voluntary and peaceful: “if you go to the south you will die” the text says, as opposed to “if you stay at the Ötüken then the caravans will come”. This is an attempt to justify the reversal of one century of Turkic history during which the Čoγay and Tögültün were the actual home of the Türks, an attempt to conceal that the change was ultimately effected by a Chinese move and a Turkic defeat. The political message of the Orkhon inscriptions is much clearer once put in this century-long perspective.

Similarly the call to Bumın and Ishtemi in these texts belongs to the same plea, to retrace a mystified Ötüken history of the Türks. In spite of the fascinating but both deceptive and highly political Orkhon inscriptions, the first nearly fifty years of the eighth century (685–743) might be regarded as a quite limited period of Turkic power in the north within a quarter of a millennium (603–840) of actual Tiele and Uyghur domination.

8 See also Suzuki 2011 for an attempt to clarify the location of Qaraqum as well as a depiction of the economic basis of the Türks in the Yinshan. My sincere thanks to Michael Drompp for drawing my attention to this article and sending it to me.

9 A side effect of this line of thought might be an attempt to identify the still mysterious Tögültün yazï of the Orkhon inscriptions. It is clear that it is associated with the Yinshan in a binomial expression “the Čoγay Mountain and the Tögültün plain”. Various scholars

have tried to localize this toponym (see Li 2011, WHO proposes a broad meaning of the whole upper region of the Huanghe including the Ordos plateau). I am wondering if the two alluvial valleys of the Huanghe and the Heihe are not to be understood under that

name: there is still at their confluence a county with the quite close name of Tuoketuo 托克托 – earlier Tuoketun 托克屯? –, and the easternmost fortified point was built around this area in 708. J. Jeong suggested to identify Tögültün yazï with the Tümed steppe (see Li 2011, 375 fn. 6), a solution rather similar to mine as the Tümed steppe is just north of Tuoketuo. The Chinese conquest would have cut the Čoγay from the Tögültün while both of them would have been necessary to sustain an imperial center south of the Gobi.

10 Differently Skaff 2012, 309 who would rather place the conquest of Mongolia between 688 and 693 due to the lack of raids on the Chinese frontier during these years.

Away from the Ötüken: A geopolitical approach to the 7th c. Eastern Türks,” J. Bemmann, M. Schmauder (ed.), The Complexity of Interaction along the Eurasian Steppe zone in the first Millennium AD, (Bonn Contributions to Asian Archaeology, 7), Bonn, 2015, s. 453-461. Etienne de la Vaissière https://www.