The discussion revolves around the study of Turkic languages and their historical connections to Japonic, Koreanic, and Mongolic languages. It explores the methods of reconstructing ancestral languages, the significance of basic vocabulary, sound correspondences, and the integration of linguistic evidence with archaeology and genetics to understand the origins and migration of these language families.

She will tell us more about the topics herself in a moment thank you very much for this beautiful introduction and thank you of course also for having invited me cesia thank you very much for this for this important question yeah linguistics is the study of language and we can study the language synchronically that is at a certain point in time but we can also study language iachronically that is the development of language over time and my specialization lies with diachronic linguistics that is i’m a historical comparative linguists and historical comparative linguists can take you back very far in time long before the attestation of the first written records basically we compare tested languages to reconstruct ancestral languages but its ancestral language has never been written down.

So we just reconstruct it and it can be separated for centuries and even millennia from the first written sources so it is this ancestral language this proto-language that we reconstruct and once that we have reconstructed then the proto language we can also have a look at the ancestral vocabulary and try to reconstruct the natural and the cultural environment of these ancestral speakers.

So if we find words say for textile technology or for crops or for certain stone tools or for animal husbandry or daring then we can also deduce that the speakers of that language were familiar with these practices and events and then linguists can also try to find out with whom the ancestral speakers were in contact we could for instance find out that the proto-turkic speakers the ancestral turkic speakers were in contact with old ironic speakers be because there are borrowings loanwords between two languages and then linguists can also build language trees and these language trees visualize how languages broke up and spread over space and over time and we can also date the notes in the tree that is we can find out at which time the different separations happened and then finally linguists can also try to locate the homelands of ancestral language families in space.

So we can find out where the ancestral speakers were located and last but not least i would say it is also important that linguists cross the boundaries of their own fields and that we put or linguistic evidence or evidence about the location and the timing and the migratory dynamics of language that we put that together with findings of archaeol archaeology and genetics archaeologists and geneticists study also variables like time and location and they also study the migratory dynamics of of people and cultures that form the object of their study.

So putting or mapping these different lines of evidence on each other we can reach a more holistic view on human prehistory then each of these disciplines can provide us with individually as possible yes reconstructing i have to here reconstructing language what we really do is we take we take contemporary forms or we take tested forms of the language we compare them to each other and we try to unwind the similarities the regular similarities back to the most recent common ancestor but if you compare let’s say languages that are very that very distant in time that have separated very distantly in time like turkic and japonic and you still find similarities then you can unwind these similarities to a common ancestor that is very deep in time in or a case that would be like 9 000 years ago like for instance you have verbs in in japanese kamu bite chu and you have in all turkic for instance and also other turkic languages this word can to bite to chew you can comparing this you we can wind that back to a common word for chem in the ancestral language or here with katai heart solid you have this word in turkic or cut also i think it’s it’s here.

So you have it in all turkic cut or cut to be hard you have it in in ver in different contemporary turkic languages like in turkish but also in uzbek and shore and dolgam and it’s even there in in chuvash in in western turkic language and all these form reconstruct back to one common ancestral form cut in proto-turkic that again can be compared to these forms in the other trans-eurasian languages so that’s how historical linguists so to say unwind regular similarities between languages yes well personally i cannot do all the work for myself of course because you have to imagine there are 59 different trans-eurasian languages.

So i cannot go on field work for every of these varieties that as you say are very intriguing and then some dialects and language varieties may preserve very ancient words and and and very useful evidence but that is left to the field workers some people in my team do field work but also in general there are linguists who specialize in one particular language and one particular variety who write word lists and who collect data and or task then as historical comparative linguists is to put together all these data sets to compare them and to try to find ancestral words underlying the similarities.

But so to say we built on the shoulders of the field workers indeed the work in the field is is very important you could say that i’m an armchair linguist sitting behind my desk but the tough work is done by all these people going out in the field and describing languages yes that’s very basic and an important question indeed this this issue this trans-eurasian issue is one of the most disputed questions of historical comparative linguistics.

So the question whether the turkic languages belong to the same family as the japonic languages and koreanic and to music and mongolia is one of the most hotly debated issues in linguistics and we use this term trans-eurasian in reference to this large group of geographically adjacent languages including here japanese and other japonic languages in purple then we have koreanic languages today only korean in yellow then we have the tungusic languages that are today almost extinguished but you see these little red spots on the map those are the music languages in red and then we have the mongolic languages here you see in blue the mongolic languages not only calca mongolian as it is spoken in the republic of mongolia today but there are about 15 different mongolian languages and then we have this vast group of turkic languages

So not only turkish turkey turkish as we know it well and as you probably are you are native speakers but a whole group of closely related languages stretching all across eurasia. So including even these turkic languages that are spoken in northern siberia like yakut and dolgan and this separate language families are relatively uncontroversial nobody would dispute that they are genealogically related to each other but the question whether all these languages go back to one single common ancestor is one of the most disputed issues in historical comparative linguistics and even if even when i agree that much of the evidence for this relationship provided in the past is questionable i still think that there is a small core of evidence that can support the genealogical relatedness of turkic to japanese korean music and mongolian languages.

So i believe that it is possible to state that trans eurasian is a valid genealogical grouping that’s a good question.

So what is the evidence for trans eurasian that is actually a question that i have been studying over the last 20 years it has been always at like the center of of my career as a linguist and to show that languages descend from a common origin we need different pieces of evidence.

So first we need to compare basic words.

So not just any words but basic words words that are universal across the languages of the world and that are relatively resistant to cultural influence to borrowing words like head mouth nose child parent eat drink moon star like this very basic words that’s the first thing we need the basic vocabulary but then we also need to compare sounds we need to find phonological correspondences sound correspondences so the words need to correspond in a regular way each sound needs to correspond regularly to another sound and then finally we also need the building stones of the words to correspond

So these little more themes or building stones that make grammatical function or that derive words from each other they need to correspond as well so that are the three pillars we need to establish linguistic relatedness and in the case of trans the eurasian as i already showed to you we find basic vocabulary that means that these basic words like the word for bite but also watch or burn or heart these basic words are corresponding and we find about 93 etymologies for basic vocabulary corresponding in addition

So as i showed the these correspondence sets are well distributed it’s not as if a word is present in only one language but it’s well distributed over the different languages of each family. So not only in old turkic but also in turkish and azerbaijani in turkmenia in uzbek in vigor and so on and even in church and then we also find sound correspondences between the different trans-eurasian languages i gave you this example of qatar heart here we see that every sound is corresponding regularly

So the k is corresponding regularly the medial vowel a is corresponding regularly and the t is corresponding regularly and those correspondences do not occur only in this word but they occur again and again in different sets so like that we can establish a list of sound correspondences consonant correspondences these are the consonant correspondences for the trans-eurasian languages but also vowel correspondences

So we have vocabulary and we have sound correspondences and actually we also find morphology my previous study that was published in 2015 was a book on the diacrony of verb morphology showing that there were there are little elements in the verbs that correspond regularly regularly as well

So for instance here there’s only one example in turkic we have a resultative nominalizer a little word that’s a little building stone that derives words nouns from verbs like you have for instance the verb to reduce and then you would have kisgah short reduced and this little ga or ka can be compared to the same element that does the same thing in other trans-eurasian languages so we have morphology we have phonology and we have vocabulary and that is why i believe that turkic is indeed relatable to japonic and the other trans-eurasian languages yes indeed that is very important as you suggest

So here this abbreviation ot stands for old turkic and all turkic is the language of the orcan in inscription so the the language that has been found in mongolia’s arkhan valley on the inscriptions of the khans dating back to the eighth century and the old turkic period stretches over old wigar the old turkic and the terran basin to the language of mahmoud al kashkari’s compendium of turkic languages which was written in the turkic

So this whole period is called old tea all turkic and we do rely on on sources in old turkic and and we add these elements to our comparisons yes between the actually there are five branches to trans-eurasian japanese korean to music mongolic and turkic and in the basic vocabulary we found in the 200 basic vocabulary we found about 150 sound word comparisons when we go larger also include cultural vocabulary there are about 340 etymologies that support trans-eurasian relatedness yes that’s very important for linguists

So most of the words relate to basic vocabulary that and in the basic vocabulary we find a lot of verbs so more words for as you say grabbing taking eating and so on more verbs than nouns than objects and this is a very important observation because we see across the languages of the world of the world that nouns are easily borrowed

So objects are re easily transferred from one language into another say from turkic into mongolia or from mongolia into turkic but verbs are much more difficult to borrow than nouns because they are more abstract and because they are inflected people will not so easily borrow a verb for instance if if turkish borrows the verb to click from english like to click with a computer it would say something like click attack or click i don’t know but it’s it would also have to accommodate for this borrowing with a special element and it’s rather rare that verbs are borrowed and it always goes over normalized form and the very fact that we find so many naked verbs shared here is therefore in support of genealogical relatedness rather than borrowing if this would be a borrowing relationship between the different languages you would find many many objects but not many verbs and in in reality we find it the other way around as you suggest many verbs and just a few nouns

So yes so in indeed when we then accept this trans-eurasian relatedness it brings us to new questions new questions arise and as you correctly point out one of the big questions is who were these speakers of prototrans eurasian who were these ancestral speakers to the turkic speakers were their ancestors where did they live and when did they live and that are questions that cannot be answered with linguistics alone in order to do that i needed to integrate other fields like archaeology and genetics into the into the into the picture and to find that out or to find the location out we integrated these different techniques but in from the linguistic perspective we collected a huge database of 98 different trans-eurasian languages we collected etymologies word comparisons for these languages both for historical stages like all turkic and all japanese but also contemporary languages like turkish and uzbek and and so on and we collected basic vocabulary and cultural vocabulary and on these languages we applied computational techniques bayesian phylogenetics to find out first a dated tree a classification of the languages but these techniques were also used to model the languages in space

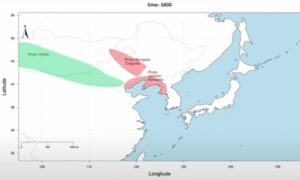

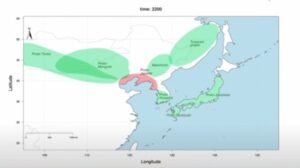

So based on this classification we let the computer the algorithm decide where the center of the spread really was and what we found converging this computational techniques with more classical techniques of homeland detection we found that the most likely origin for the five different groups was probably situated in northeast china in the west liao river area and the first split into altaic which is which is turkic mongolia and to music together and japan ocorianic happened there

And so japan went to the audung and then you see turkic splitting off very early i think six thousand years ago already turkic goes into the stepper then koriyanic goes to the korean peninsula tungus to the russian far east and finally japonic moves over korea to japan so that was how how we modeled this this dispersal in space that’s a very good and relevant question cyano tibetan is the ancestor of the synthetic languages chinese and also the tibetan languages

So the language is also spoken in the himalayas and so on they all go back to one common ancestor and recently in 2021 there was a study in nature that suggested and confirmed earlier studies that the ancestor of the sign of tibetan languages is probably situated here as a neighbor to trans eurasian in what we call the yellow river valley so bits to the south of trans-eurasian linguistically there are no indications that cynotin is related to trends eurasian but what we find is probably very early ancient borrowing out of borrowings at a very early level

So we think that cyano tibetan was situated in the yellow river area around 8 000 years ago and that it was therefore contemporaneous and nearly adjacent to the speakers of trans-eurasian so most probably there was some exchange between those speakers but they don’t go back to a common ancestor at least not one that we can demonstrate you can never know of course but relatable or related in linguistics is relatable only what is relatable with the methods can be related professor roberts thank you for your knowledge we learned a lot of things from you i wish to learn you are saying mongolia japanese korean and turkish and other some language was burned same area but normallyone of the origins which one is the origin because the mole foreign we cannot put it like that but we can say that turkic has a common origin with japanese korean tungusik and mongolic

So all these languages are sister languages that go back to a common mother but we cannot say that turkic is the mother turkic is the sister and the different languages go back to one common ancestral language of course the reason why the turkic languages became so spread across eurasia is something that happened much later and that is the adoption of pastoralism

So first the the ancestors of the turkic speakers were probably farmers millet farmer farmers but around 1000 bc so 3 000 years ago a pastoralism was important from the western step to the eastern step and it is probably there that the turkic speakers adopted pastoralism added pastoralism to their agricultural knowledge and due to pastoralism and horse riding they were extremely mobile and from the bronze age onwards they spread all across eurasia and that is what caused this picture today where you find the turkic languages all spread from turkey in the west to yakut in the in the northeast

So they were extremely good question i’m not a specialist in chinese but just recently i hired a doctoral researcher who is she is chinese and she’s a specialist in old chinese reconstruction and our goal is as you suggest to find out whether we can find evidence for very early borrowings between trans eurasian and cyano tibetan but not borrowings that go back to the bronze age or later but really very early ones that are perhaps going back to the beginnings of agriculture and the exchange of of agricultural practices i don’t have a picture of them but i understand where you’re going you’re going into the archaeology and and into the culture i cannot comment on this specifically but indeed one of our goals the goals of our study was then not only to compare the languages but also to compare the culture the different cultures of the different populations and there that was of course a huge challenge for me because as a linguist i knew about the the timing and the space of the languages and about the migra migratory dynamics of the languages but one of the big challenges was how now can we combine that with findings from genetics and from archaeology and one of the basic ideas that under light or research was an independent collection of data and an independent analysis of data

So the archaeologists like here or archaeologist mark hudson he went out in the field and collected archaeological data and performed archaeological analysis independent from the geneticist and the linguist so our geneticist like here ningxiao went out in the field collected samples skeletal remains independently from the other ones and like that each one collected his data and did his analysis and only in the final phase we brought the different lines of evidence together

So for instance in in the case of the are in of archaeology we scored different features relating to ceramics to stone tools to buildings to plant and animal remains to shell bones and and artifacts and also to burial

So perhaps the bubble are somewhere in but i’m not sure so we had say 172 features that we compared across all these different archaeological sites

So we had neolithic sites and we had bronze age sites and we scored all these sites for the features and then we applied also these computational techniques to the different cultural features and basically what we found confirmed that millet agriculture originated here in the westlake river area so we find the origins of millet agriculture exactly where we find the origins of the trans-eurasian languages and from there a millet agriculture dispersed to korea six thousand five hundred years ago and to at the russian far east five thousand years ago and then later rice agriculture was integrated and it moved from this liaodong shandong interaction sphere over korea to japan where it caused a big turnover from hunter-gatherers german people two yayoi people to farmers and the turkic people were probably also millet farmers they lived here split off went more here and then only in the bronze age they started to spread all over eurasia so in in this way actually we found that millet was the big archaeological shared component

So where at the speakers of trans-eurasian share trans-eurasian ancestry as a common linguistic component they should all share millet agriculture as a common agricultural component cultural ethnic personally i do not make that kind of research but i think it’s extremely interesting of course to to understand the origins of the script but as you correctly point it out you say you you stress the word symbol so script is a symbol for spoken language so many people have spoken language but they don’t have script

So what we try to focus in on is attested spoken language and to wind it back to spoken language in pre-history so to say so we are not so much well yes as you as we discussed so far we have been searching for commonalities for similarities common elements between the different speakers of trans-eurasian languages

So we have discussed today that we found this common trans-eurasian linguistic ancestry to for the trans-eurasian populations we have seen that we find a common component in the archaeology namely the millet farming and then our geneticists also found that there was a common component which is called amor genetic profile that is shared by the different speakers of the trans-eurasian languages so so far we can say yes there’s a common component two trans-eurasian speaking populations both genetically linguistically and archaeolic archaeologically however what would interest me for the future is to turn our perspective upside down

So to say so instead of looking at the common component and identifying a common component we could move away from that and study the differences because especially from the brown late neolithic and bronze age onwards we see that all these trans-eurasian populations start to spread all across eurasia and doing

So they meet non-trans eurasian populations speakers of other languages with different genes and this leads to a fascinating picture of mixing mixing genes genetic and mixture for instance the turkic populations go on the step they meet they meet people of west eurasian ancestries and we see gradually in a mixture of east and western genetic profiles for the turkic population

So gradually they mix with western eurasian populations and at the same time that they are going to mix genetically we also see that their agriculture is complemented with pastoralism

So also culturally they are going to mix and we see that their language that that turkic also has very ancient borrowings relating for instance to pastoralism or horse or horses from ironic and from tarkarian

So this whole picture of mixing mixing genes mixing subsistence strategies and mixing language is something which i find really fascinating and which i would like to study in the future of course not only for the turkic languages on the step but also for north east asia what you mentioned this mixing between sino-tibetan and trans-eurasian populations is extremely interesting what happened in the russian far east with speakers of nifkof paleo-siberian languages and and speakers of trans-eurasian languages coming on top of that and then what happened in korea and japan with the original german populations hunter-gatherers that then are going to mix with incoming farmers

So it is this mix and match that i would like to study in the future which is very interesting i think first of all that you’re very well informed the the thing is that not so much in the vocabulary in the words but certainly in the language structure people have suggested linguistic related relations across the bering street we have for instance one researcher eduard fajda who has found that the cat language a paleo-siberian language from central asia is probably related to the nadene and niniseian languages spoken on the north west pacific coast in the americas

So there are certainly relations there the only problem is that these relations go back deep in time 10 000 years ago and deeper and with our classical linguistic methods so studying words and morphemes as you suggest we cannot go back deeper in time than 10 000 years ago

So there we are a bit on the limit of what classical linguists can do however there are also linguists like joanna nichols and balthazar bickel for instance who try not to look at words but look at structural features of language like yes no features of language does the language has verb in the end or not is the language polysynthetic or not that kind of of features they study and from there they also suggest what you say this linguistic relationship across the bearing straight straight which goes back 10 000 years ago and and earlier but that is not so much my field i’m a classical historical linguist and therefore i i must focus on everything what is before 10 000 years ago professor roberts is some special place very very old times more than 10000 years ago if you have a time we are awaiting you in turkey thank you very much for your stimulating suggestions and for your advice professor i must say i take your offer and i will certainly come to turkey so reportage thank you thank you so much for this interesting and stimulating talk thank you thank you thank you martin roberts